Abstract

This study sought to measure differences in participants’ ability to solve a classic logical reasoning problem, the Wason selection task. The participants consisted of 29 university students. The experiment replicated a traditional version of the task via digitized form. Experimenters manipulated the variable of how logical reasoning problems were presented, either abstractly or thematically, to determine which flavor of such logical reasoning problems the participants would be able solve most accurately. Researchers hypothesized the thematic-content versions of the logical reasoning problems would be solved correctly markedly more often than the abstract-content versions, replicating firmly established results. Results were not supportive of the hypothesis, as data showed an unexpected similarity in the results that did not reflect the traditionally expected differences.

Keywords: logical reasoning, abstract reasoning, Wason selection task

Replicating the Wason Selection Task: Experiential Provisioning

The Wason selection task, in its most basic form, is a test of the ability to solve a simple logical reasoning problem. There are many variations, replications, and permutations derived from the original Wason selection task. The second experiment in an original study by Wason and Shapiro (1971), “Natural and Contrived Experience in a Reasoning Problem,” deals specifically with the application of abstract content and thematic content to the logical reasoning problems that comprise the experiment’s core. Having produced notable and longstanding results, a replication of the Wason selection task can be an exercise of witnessing consistency within the peer-reviewed scientific process.

In the Wason selection task, test subjects are shown the fronts of cards containing some variety of information, and then asked to prove if a given a logical rule is true or false by checking the reverse of some of those cards for additional information needed to validate the rule. In base logical form, the rule could be (and often is): “if p, then q.”

In one half of a prototypical Wason selection task, ‘p’ and ‘q’ are often represented abstractly, with letters and numbers being substituted for the logical notations of ‘p’ and ‘q.’ The traditional number of four cards presented might show the letters ‘G,’ ‘H,’ and the numbers ‘7’ and ‘8,’ with one character on each card, and another character on the reverse face of each card. Participants are then given a rule, such as “If a card has a ‘G’ on one side, then it has a ‘7’ on the opposite side.” Participants are asked to prove if the rule is true or false. Most participants would select the cards with ‘G’ and ‘7,’ though there are many incorrect combinations. Selecting the ‘7’ card is incorrect, as there is no rule stating that a ‘7’ card must have a ‘G’ on the reverse face – just that a ‘G’ card must have a ‘7’ on its reverse. Selecting the ‘8’ card to see if it has a ‘G’ on the reverse can falsify the rule if a ‘G’ appears, since the rule stated that if there was a ‘G,’ there must be a ’7.’ Choosing to check the card with an ‘H’ cannot confirm or falsify the rule about cards with a ‘G’ on one side either, so it is irrelevant. Common mistakes can be attributed to participants’ biases. Confirmation bias, matching bias, or other biases, if present, are subjective to each participant and beyond the purview of this study.

The other half of a prototypical Wason selection task hinges on the application of participants’ knowledge and experiences, contrasting the pure logic required for abstract-content trials. Reworked with thematic contents, the reasoning problems are otherwise identical in the logic required to solve them. In place of letters and numbers, thematic-content versions of the selection task use ideas or concepts germane to participants’ lives.

An example of thematic contents in the Wason selection task could involve legal drinking ages: most people know through either knowledge or personal experience of exactly how old they must be to legally purchase or consume hard drinks. The premise of these cards might be “each card has a kind of beverage experience on one side, and an age in years on the other.” The four cards might display “Wine tasting,” “Mocktail,” “16 years of age,” and “32 years of age.” The logical ‘rule’ to be proven could be: “If a person is legally interacting with hard drinks in the United States, they must be at least twenty-one years of age.” To check if the rule is true, the first card, “Wine tasting,” and the third card, “16 years of age,” are the correct choices. The card featuring ’32’ is irrelevant (well above the legal drinking age), and the “Mocktail” card would be a zero-proof selection available for all. Flipping the “Wine tasting” card – only to find an age below twenty-one – could falsify the rule, as could finding “A case of fine shiraz” on the reverse of the “16 years of age” card. In these examples, the correct selections in the abstract example correspond precisely to the correct selections in the thematic example.

It is accepted as a truth that applying knowledge and experience to thematic versions of the reasoning problem allows participants to deduce the correct solution more often – even though the underlying logic is unchanged. The percentages of correct or incorrect responses to either the abstract or thematic components of course varies slightly across the countless iterations of the Wason selection task, spanning several decades, yet participants historically show far more correct responses in thematic-content trials. A study on rationality, sourcing its data sets and results from many instantiations of the Wason selection task, illustrates this trend as a peer-reviewed truth (Oaksford & Chater, 1994).

Some researchers have wondered if the amount of personal experience or the breadth of personal knowledge of study participants might affect the results of the Wason selection task. At the University of Florida, researchers expanded upon the original Wason selection task in attempts determine if more-experienced individualswould score higher on the thematic portions of the test (Cox & Griggs, 1982). They found that participants who had more life experiences, when related to the thematic versions of the task at least, were indeed more likely to be able to solve those problems. Cox and Griggs also discovered that some high-experience participants sometimes answered correctly or incorrectly more often than expected in certain trials, but only when repeating an individual trial that shared a pattern with another trial. They concluded that participants’ intraexperimental experiences were an additional factor – participants had created heuristics over the course of many trials, producing these novel results.

It is of interest that so many academic and professional specialties continue to draw from the selection task. In The Adapted mind: evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture, the report “Cognitive Adaptations for Social Exchange” attributes the increase in correct thematic-content trials to evolutionary psychology (Barkow et al., 1992). The authors also use Wason selection task results to bolster their own theories about social elements linked to evolutionary psychology. They suggest that certain social traits, intrinsic to the human condition, make it easier for people to solve the thematic-content trials due to the human ability to find exceptions to social rules. They make a complex case in favor of evolutionary psychology’s impact, though proof of an evolution-driven social component (against many other kinds of social components or non-social explanations), as the engine behind typical Wason selection task results, is ultimately difficult to prove.

Oaksford and Chater (1994) collected and analyzed data from many experiments and studies that had replicated the Wason selection task in their “A Rational Analysis of the Selection Task as Optimal Data Selection,” which questions at one point whether human beings are truly “rational” (as defined by logical terms). They subjected the data sets from past studies, each completed by different researchers or groups, to mathematical analyses of the core logic found within the reasoning problems used, and an analysis of the statistical results across those collected studies. Ostensibly a meta-analysis, they concluded that defining human beings as either rational or irrational, when based on performances on logic puzzles, is not a reasonable metric. They reiterate that while the logic may appear to be the same between abstract-content and thematic-content versions of the selection task’s trials, the kind of reasoning actively applied to each really is quite different. Their inquest into human rationality was essentially fueled by results from the Wason selection task, yet another example of the task’s importance among many others in existence.

The consistency of the Wason selection task is, again, generally stalwart, making it a fine choice for the purposes of replication. A replication of the experiment was conducted to witness the task and its results firsthand. Considering that it is known that thematic-content trial responses generally produce more correct responses, any hypothesis should stand with that of the original task. The experimenters hypothesized that participants would be better able to solve logical reasoning problems when the problems were presented thematically, germane to their knowledge and life experiences. The methods section of this study will describe the computerized version of the traditional experiment utilized. The discussion section will offer suggestions and criticisms that are perhaps unique to the brief and digitized version of the experiment in addition to standard analysis and discussion.

Method

Participants

The sample was comprised of 29 adult university students attending The University of Virginia. Participation in this study was a component of a course in cognitive psychology reputed for excellence, conducted remotely via the worldwide web.

Design

Experimenters created several series of cards and paired each series of cards with a logical statement. Each series of cards consisted of four total cards – one set for each trial. In each trial, the paired logical statement acted as a potentially falsifiable rule. In each trial, participants were tasked with examining the front faces of the cards to deduce which two of those cards contained additional requisite information on their reverses needed to validate the rule. Through selecting the necessary cards to prove or falsify the rule, participants would illustrate their understanding of the logic needed to solve the problem presented in each trial.

Varying the kinds of information in the trials acted to test if participants were better or worse at validating a given rule, presented either abstractly or thematically. Therefore, half of the sets of cards in the experiment were presented with only letters and numbers (the logic framed through abstract content), and the other half with only ideas or concepts relating to knowledge or experience (the logic framed within thematic content).

Considering each trial contained only thematic or only abstract cards, the independent variable in the experiment was the type of content used in each trial. The dependent variable in the experiment was the mean number of cards that the participants could correctly select while solving the problem. The participants’ scores were measured by the number of correct card selections in either of the two subtypes of trials.

Procedure

Each student participant was given a brief overview of the nature of the Wason selection task: Participants would be presented with abstract-content cards in half of the trials and thematic-content cards in the other half of the trials. All abstract-content cards contained an Arabic numeral on one side, and a letter (from the Roman alphabet) on the other, while the thematic-content cards would contain ideas or concepts related to common knowledge or experiences, varying by trial. In each trial, participants would see a rule, and four buttons corresponding to the four physical cards traditionally used for the task. The rules shown to participants were phrased either thematically or abstractly, matching the two subtypes of card series. There would be three trials of each subtype over six total trials. The entire process would be conducted through the same web portal that provided the background and instructions.

Just before beginning the trials, participants were reminded that the full field of the experiment’s window would need to be visible in their web browser; being able to see all necessary information was essential before clicking “begin” to initiate the trials.

Once the trials began, participants were asked to choose the two cards that contained the necessary information on the reverse faces to prove or falsify that trial’s rule, as previously described. After identifying their selections of the correct cards, participants were asked to click or tap on their selections via their web-enabled device. Participants were reminded that once they had selected a card, their selection was final. After submitting their choices, participants were asked to do the same for each additional trial.

At the end of the experiment, participants were given the option to add their results to the global data set before they were redirected to a results page. The results page displayed an automated analysis for their results, the group’s results, and the global results.

Results

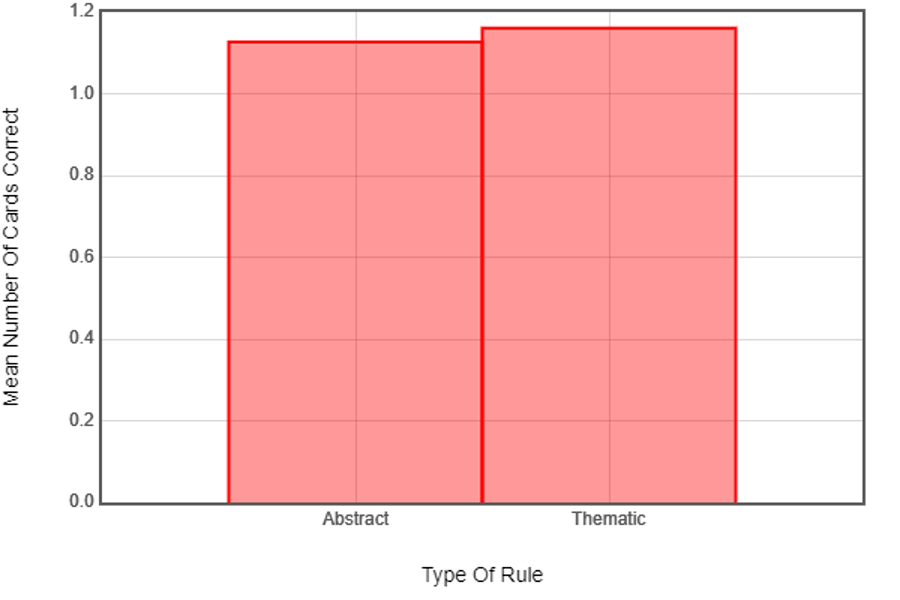

Participants performed only slightly better when the conditions of the trials contained rules paired with cards of a thematic nature, M=1.161, SD= 0.341. Participants performed only slightly worse in the trials with abstract conditions, M=1.126, SD=0.326.

Discussion

The Wason selection task and its variations have proven to be consistent and valid for many decades. These tasks usually produce results that clearly show higher scores for thematic-content trials in comparison to the abstract-content trials. In this study, while it was hypothesized that participants would perform much better in the thematic-content trials, this was surprisingly not the case. The results for both subtypes of experimental trials were startlingly similar, the expected disparity missing: participants chose nearly the same number of correct answers for abstract-content trials as for thematic-content trials.

There are some potential problems with the experiment which may have been contributing factors to the unexpected results. The overall complexity of this computerized instance of the Wason selection task is low, creating less room for participants to answer in error (or increasing the chances of an accidental correct response – depending on the optics applied to four choices with two correct responses). The software provided may have randomized the order of the six trials, acting as a control against any bias involving the order of the trial subtypes, and this feature should be added if it is not present. The content of each trial would benefit from automated randomization: a simple software script could process the rules and content necessary for the trials and then randomly generate unique card/rule pairs for each new instance of a trial.

The sample size of 29 student participants can be considered small, though the size of the sample is most likely not the primary flaw in the experiment, as the unexpected results are not statistically likely to be sheer coincidence. The number of trials, six in total, is also very low, so increasing the number of total trials for each condition would help to create better sets of results.

The experiment may have benefitted from a manipulation check regarding the effectiveness of the independent variables used. No matter the root factor(s) potentially involved, checking for and increasing the effectiveness of the independent variables would most likely be the wisest first order or business before replicating this experiment a second time. The repetition of the logical argument in each trial is perhaps the most problematic aspect of this experiment, as each trial appears to follow the same pattern of logic. If a participant had confidently solved one abstract-content trial and one thematic-content trial, they could easily provide correct responses to all six trials with very little additional thought. This may have raised the mean for the abstract-content trials to unexpected heights. Some participants verbally reported during a class discussion that they felt they had to solve only one logical reasoning problem six times, that each problem felt like it was the same (which they were, as intended). Increasing the total number of cards and varying the rules’ pattern of logic (e.g., stating the contrapositive of the premise instead of the premise itself) could help to add difficulty, thus shifting the overall results.

A thorough manipulation check could potentially address all the above concerns when ensuring the independent variables are functioning as expected, though all concerns raised deserve attention in reworking the framework of the experiment. It is unlikely that this experiment has discovered a groundbreaking result or uncovered an overlooked nuance of the original Wason selection task. If traditional results are expected, this replication experiment becomes a lesson of how to better design a web-portal based iteration of the original task and is invaluable in terms of the perspective it creates and as an experience.

References

Barkow, J. H., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (Eds.). (1992). The Adapted mind: evolutionary psychology and the generation of culture. Oxford University Press.

Cox, J. R., & Griggs, R. A. (1982). The effects of experience on performance in Wason’s selection task. Memory & Cognition, 10(5), 496–502. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03197653

Oaksford, M., & Chater, N. (1994). A rational analysis of the selection task as optimal data selection. Psychological Review, 101(4), 608–631. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.4.608

Wason, P. C., & Shapiro, D. (1971). Natural and contrived experience in a reasoning problem. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 23(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335557143000068

Appendix

Means Number of Cards Correct for Abstract and Thematic Trials

You must be logged in to post a comment.